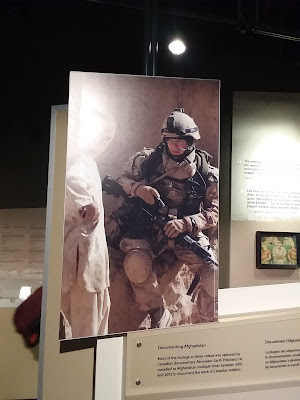

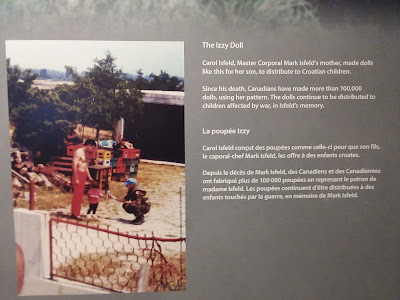

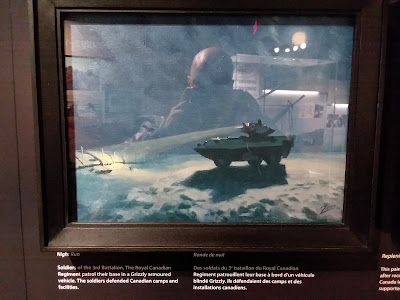

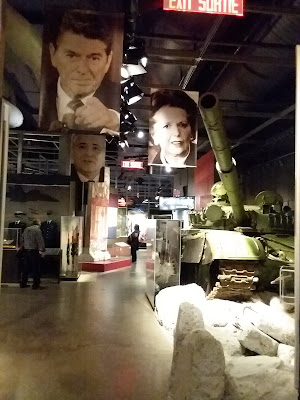

A video display panel shows images of the Afghan War, including a tank, seen here.

Monday, January 31, 2022

The War That Was Left Unfinished

Sunday, January 30, 2022

Yugoslavia And Afghanistan

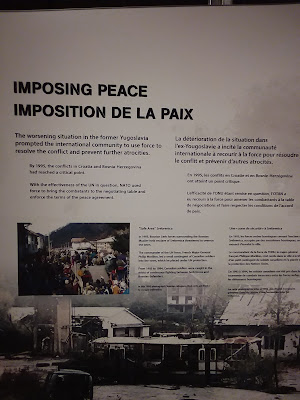

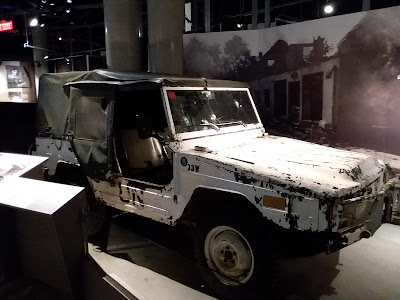

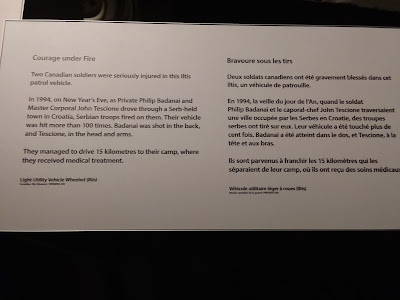

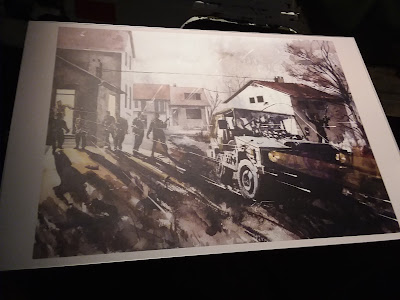

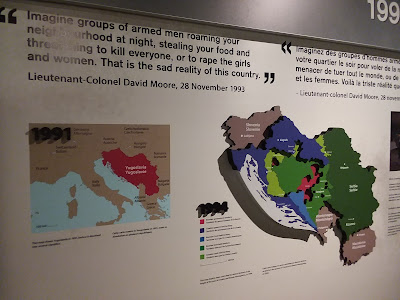

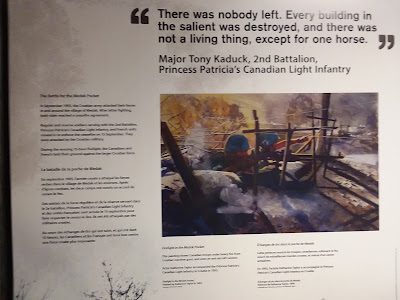

The mission to the former Yugoslavia would eventually become a NATO mission to stop the atrocities. Canadian forces remained involved throughout.

Saturday, January 29, 2022

Genocide And Civil War

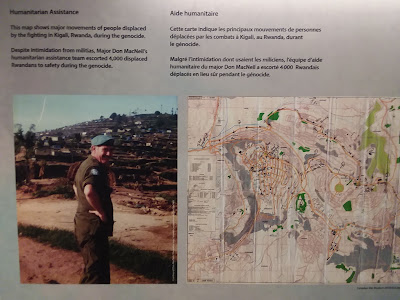

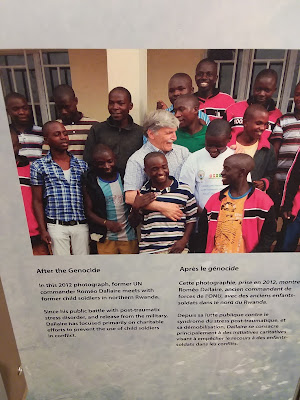

Tensions in Rwanda had persisted for years, resulting in the establishment of a peacekeeping mission in 1993. Lieutenant-General Romeo Dallaire commanded the mission for nearly a year, and during this time the civil war exploded into genocidal bloodshed. Dallaire and those under his command did what they could, but could only bear witness as the world didn't really understand what was happening until it was too late.

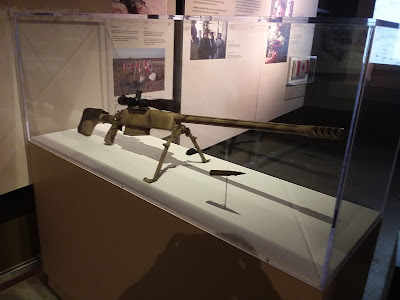

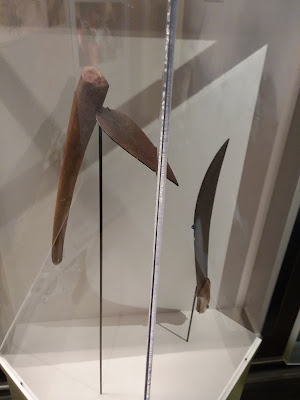

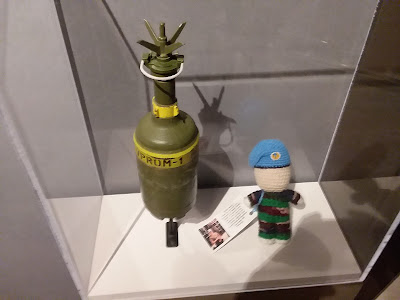

Weapons used in the genocide speak for themselves.

Friday, January 28, 2022

New World Disorder

Thursday, January 27, 2022

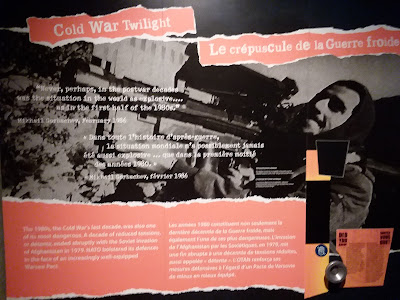

Cold War Twilight

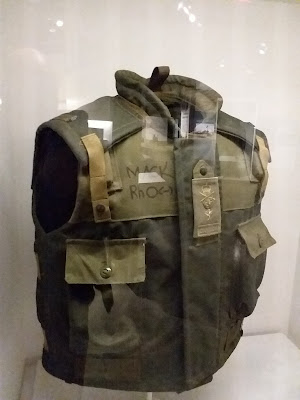

Here we have two standard uniforms. One dating back to the Cold War period is a field uniform, not really that different from what one might see today.